You are reading the archive for the category: Historical Fencing

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing with 7 replies

(10/1/2009)

LINK TO ARTICLE 1

LINK TO ARTICLE 2

LINK TO ARTICLE 3

Hand Positions

In the Italian tradition the hand positions are notated as first, second, third and fourth. While this is concise, it doesn’t provide any information that guides the student to the correct position without additional explanation. When grasping a sword, we can discuss the same hand positions by the orientation of the fingernails. By using the fingernails as a reference, the Spanish system achieves a very simple notation for the position of the hand in plain language.

Fingernails Down (uñas abajo) – The edges are in the horizontal plane with the true edge on the outside line and the fingernails facing downward. This is the same as Italian Second. Carranza considers this position one of the two possible extremes that will be weaker than the moderate halfway point between this position and fingernails up.

Monica's hand is fingernails down.

——————————

Fingernails Inside or On Edge (uñas adentro or de filo) – The edges are in the vertical plane with the true edge low and the fingernails facing toward the inside line. This is the same as Italian Third. Carranza considers this the best position and it is halfway between the two extremes of fingernails up and fingernails down.

Monica's hand is fingernails inside.

——————————

Fingernails Up (uñas arriba) – The edges are in the horizontal plane with the true edge on the inside line and the fingernails facing upward. This is the same as Italian Fourth. Carranza considers this position one of the two possible extremes that will be weaker than the moderate halfway point between this position and fingernails down.

Monica's hand is fingernails up.

—————————–

Fingernails Outside (uñas afuera) – The edges are in the vertical plane with the true edge high and the fingernails facing toward the outside line. This is the same as Italian First and while it is mentioned, using this hand position is so unusual that Pacheco and Carranza typically speak only of the other three.

Monica's hand is fingernails out.

Hand Position in the Spanish Stance

The primary sources indicate fingernails inside or sword on edge is the hand position used when assuming the stance.

Carranza’s Description of the Position of the Sword Arm from The Philosophy of Arms… p. 155-156 (1569, pub. 1582):

| “And the best of all these positions is as the arm originates because in it the nerves are more relaxed and the action of the Muscles—which are (as it is said) the instruments of the voluntary movement—quicker. In this position the strength endures longer, and since it is the middle (according to necessity) one passes easily to the extremes. For these reasons and others that come from these, the position on Edge is stronger and better than the one with fingernails down or up. Between the extremes there is advantage, like in those extremes that the virtues have (as we will mention in its place), because the extreme that the Fingernails Up arm makes is not as strong as the position of Fingernails Down. Thus, of the two, Fingernails Down is the most noble because it strains the Nerves less to maintain the strength, because even though the arm does not move (seemingly) the Muscles are working inside that maintain it in that position….” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

To explain this passage, hang your swordarm normally at your side and then reach forward as if shaking hands. A natural extension places the weapon arm as it “originates” with the fingernails facing the inside. If you extend your arm with the fingernails in you are halfway between the extremes of fingernails down and fingernails up which allows you to engage with your true edge quickly as needed.

You should also note that the text explicitly indicates fingernails inside is stronger than fingernails up and fingernails down. Coming into guard fingernails up or fingernails down contradicts the author which is our primary source. Carranza provides us with a ranking of the hand positions with fingernails in as the best and fingernails up as the least strong or worst of the three.

- Fingernails in or sword on edge (Best)

- Fingernails down (better than fingernails up)

- Fingernails up (worst and least strong)

(Carranza does not discuss fingernails outside in this passage and by its omission we might assume it would qualify as the least useful position.)

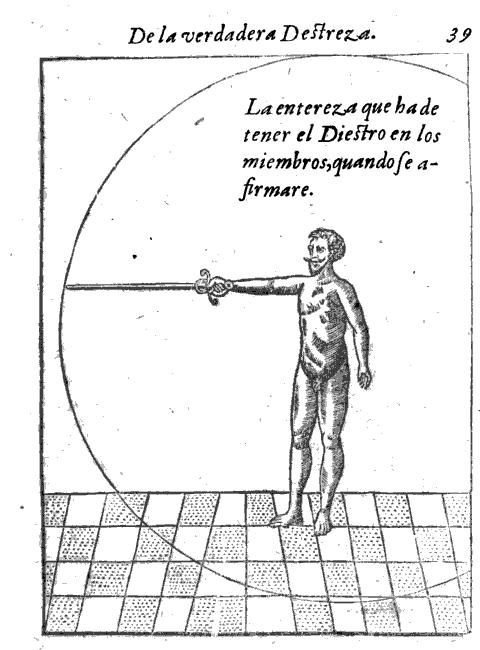

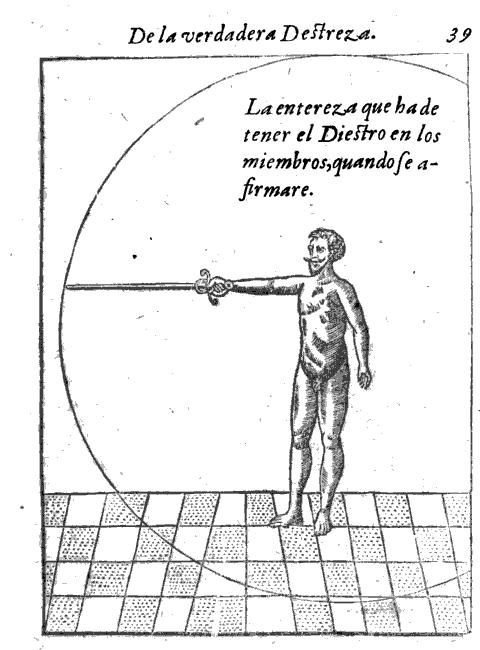

Pacheco’s Image of the Stance from The Book of the Greatness of the Sword p.39 (1600)

Pacheco's Stance showing the hand with the fingernails inside.

Pacheco again in New Science p.30 (1632)

| “The right angle is seen with the body being straight, and over the right angle or over the parallel lines, and he extends the arm straight as it originates from the body, without lowering it nor raising it.” |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Ettenhard’s Description of the Position of the Sword Arm from Compendium of the Foundations… p.13 (1675)

| The first thing that one should deal with is the way to form the Angles, with the application of the Geometric measurements; and beginning with this, I say: That the Swordsman forms the Right Angle when he stands with the body straight and perpendicular; as he naturally falls over both feet, leaving a half foot distance between one heel and the other; and then holding out the arm and Sword straightly, like it originates from the body,… |

~Translated by Mary Curtis

Over 100 years later, we see that Ettenhard comes very close to quoting Carranza in his description of how to assume the stance with the arm extended “like it originates from the body“. When comparing the text to the relevant image in Treatise 2, Chapter 1, we see Ettenhard’s fencer with the hand fingernails inside which further confirms the interpretation.

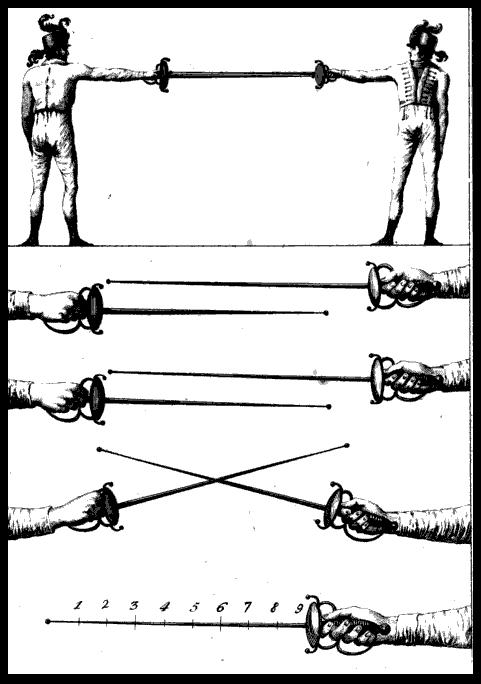

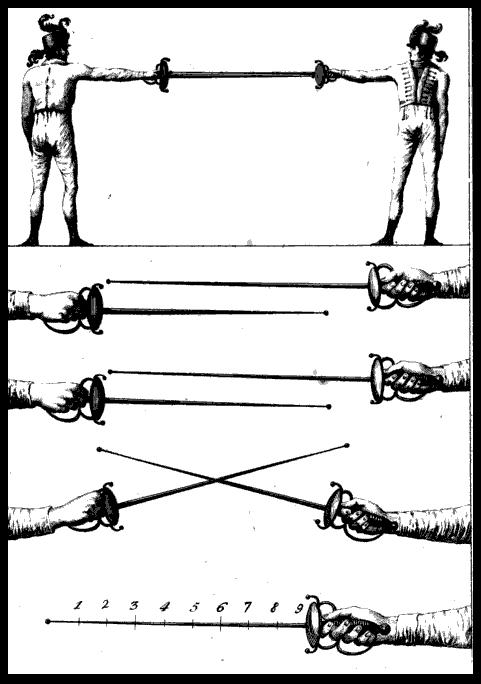

Brea’s Images in Universal Principles… Ch12.L7 (1805)

In 1805, Manuel Antonio de Brea shows the stance in his book again with the hand fingernails to the inside.

Brea shows the hand position in the stance with the fingernails facing inward for this demonstration of the Measure of Proportion and the Degrees of Strength in the weapon.

You can view Brea’s Universal Principles and General Rules… online with Google Books here:

Thibault’s Academy of the Sword Ch43 – Plate 12 (1630)

Even Girard Thibault, who is arguably outside the mainstream Spanish canon, demonstrates his stance with the hand fingernails in. Because of the peculiarity of his grip, Thibault’s cross is aligned in the horizontal plane, but the hand again follows Carranza’s advice extending as the arm originates with the fingernails facing the inside line.

Thibault's stance with the hand fingernails in and the cross in the horizontal plane

Wikipedia Article with two images of Thibault’s intricate plates

Conclusion

The repeated examples in both the texts and original images provides compelling evidence that assuming the stance with the weapon hand in a position other than fingernails inside would be a significant deviation from the tradition. While the hand position may naturally change in the course of an encounter by starting between the two extremes of fingernails up and fingernails down, the Spanish fencer is able to quickly change the position of the hand to align the true edge as needed while fencing.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, Geek Stuff, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier, Opinion with 11 replies

(9/28/2009)

Image from Swetnam

“…yet regard chiefly the words rather than the Picture.” ~ Joseph Swetnam

First, a postulate is to maintain or assert that something is self-evident. It is part of the fundamental element or basic principle of a logical argument.

Second, a primary source is an original text (like a fencing manual) or an object (like a sword). We will use a primary source to draw conclusions about a topic. A fencer might study the book of Salvator Fabris to understand Italian rapier. Darkwood Armory might study a rapier from the original time period to understand how to create a training weapon for fencers today.

In our case, a primary source is important in identifying the origin of the information we want to interpret. Primary sources are given greater value than secondary sources. A secondary source is information or discussion of the primary source that is not originated from the primary source. For example, you could argue that our recreation of Destreza based on an English translation is a tertiary source because it is based on a secondary source (the English translation).

This becomes tricky in a fencing manual when we consider the images. For example, Ridolfo Capoferro’s work has been subjected to some intense scrutiny in this regard and I have been involved in some heated discussions about the position of the feet, the nature of offline steps, and the gaining of the weapon. While the plates in the text are very important we need to remember Joseph Swetnam’s advice.

“…yet regard chiefly the words rather than the Picture.”

I call this Swetnam’s Postulate. Unless the fencing master himself is listed as the artist, the images are not a primary source of information but rather a secondary source.

Interpreting a Text

When interpreting a fencing text, I use a hierarchy of sources in which item 1 is given the highest priority and item 7 the lowest.

- The text in the original language is a primary source.

- Swetnam’s Postulate – Unless we can prove the master created the images, the artwork is a secondary source.

- The translated text is a secondary source.

- Masters in the same tradition, weapon, and time period can provide insight to technique.

- Masters in the same tradition, weapon, and a different time period, can also provide insight.

- Masters in the same tradition with similar weapons (for example classical Italian fencing) can provide insight.

- My own experience or experimentation.

For example… If Capoferro indicates that I should travel directly forward on the line of direction, I should obey the text even when it contradicts (or seems to contradict) the images rather than reinterpret the author’s instructions based on my understanding of pictures created by an artist. If other sources within the tradition also seem to confirm Capoferro’s text, rather than a picture that could arguably be on the line or off it, this provides us additional incentive to trust the author’s voice.

Likewise, as an interpreter, I need to be aware of my fencing biases and try to avoid item 7 as much as possible. When I change ‘canonical‘ technique or add technique of my own this needs to be clearly stated in my interpretation. (In this sense, I use the term ‘canonical‘ to indicate a deviation from the original text or texts.)

For example, at WMAW 2009 I applied principles from Ettenhard’s book in order to create new techniques appropriate for left-handed fencers. When I demonstrated these variations to the class, I made certain to explain that these were my variations and not Ettenhard’s original work.

By expressing some dissatisfaction with the images in his book and asking the reader to give his words precedence over the plates, Swetnam reminds us that the author’s voice is the first and primary source of information an interpreter should consider.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Fencing, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier with no replies

(9/6/2009)

With WMAW next week, I am going to do the blog equivalent of a punt and direct you to the fencing blogs of some friends of mine.

Chris Holzman is a classical Italian fencer whose book The Art of Dueling Sabre is coming out very soon from Swordplay Books. His work is absolutely first rate and the book is hotly anticipated.

Swordplay Books

Chris has a cooking blog here:

Fencers+Knives+Heak = Cooking

Kevin Murakoshi is a classical Italian Provost at Arms and a coach at the Davis Fencing Academy. His blog contains a lot of images from the Fencing Masters program examinations as well as notated rapier lessons.

Gumby Fencer

Both David Coblentz and Dori Coblentz are classical Italian Instructors at Arms and David maintains a blog primarily focused on Italian rapier with some videos here:

The Coblog

You can expect more swordplay articles from me after WMAW.

~P.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), Fencing, General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier with 9 replies

(8/31/2009)

LINK TO ARTICLE 1

LINK TO ARTICLE 2

Other Martial Traditions

In Aikido the term “Ma-ai” refers to the distance (or interval) between two adversaries. Distance in Aikido is set by your adversary’s ability to strike you. If the adversary holds a weapon like a knife, Ma-ai distance is increased to account for the greater range of the threat.

By contrast, in the Italian fencing tradition distance is typically understood as the distance your attack must travel to strike the adversary.

Close Distance or Narrow Measure– Without moving the feet the adversary may be struck by extending the weapon arm.

Correct Distance or Wide Measure– The adversary may be struck with a lunge.

Out of Distance – The adversary cannot be struck without moving forward.

The key difference between the Japanese measure and the Italian one is the emphasis it places on the conflict. The practitioner of Aikido evaluates the distance needed to defend oneself and the Italian evaluates his own ability to strike. Each martial artist will evaluate offensive and defensive measure, but the measure which is codified provides us an indication of the focus of the art.

The Spanish break distance down into two separate categories using both the concepts of defensive distance used in Aikido and offensive distance used in Italian fencing. Like the Aikido practitioner, the first measure of concern to a Spanish fencer will be the defensive distance.

The Measure of Proportion (Defensive Distance or Place)

(En español – Medio de Proporcion )

This is the closest distance to the adversary in which you may still effectively observe and react to possible threats. The Measure of Proportion should consider the weapon being used by the adversary and their physical stature. It is very unlikely that two opponents will have exactly the same Measure of Proportion.

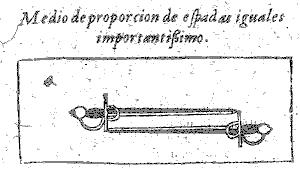

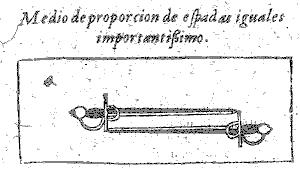

When Pacheco defined the Measure of Proportion he used the relationship between the two weapons as his guide. He advocates setting the distance so that when the adversary extends his arm at full reach, the point of his weapon reaches no further than the cross of your own weapon. If two opponents have equal bodies and equal swords, they will share the same Measure of Proportion.

"Measure of proportion when the swords are of equal length - very important" - Pacheco

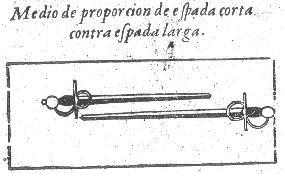

If the opponent has a longer weapon, how you set your own distance should change and your goal becomes to prevent the adversary from closing the distance so that their threat passes the cross of your weapon. The physical size of the adversary is also considered when setting the distance. For example, an opponent with long legs will have a long lunge and the Measure of Proportion will change to compensate.

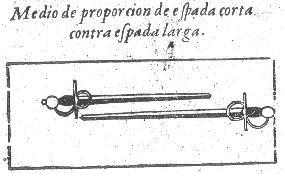

"Measure of proportion for a shorter sword against a longer sword." - Pacheco

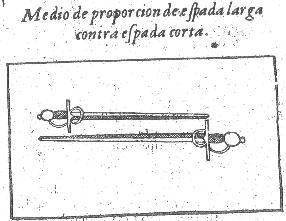

When your weapon is longer than the adversary’s your goal in setting distance is to close measure enough to maintain your own Measure of Proportion while violating the defensive distance of your adversary and continually keeping them threatened.

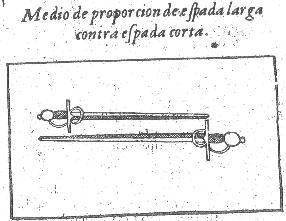

"Measure of proportion for a longer sword versus a shorter sword" - Pacehco

Ettenhard, one of Pacheco’s students, later provides a more nuanced description of this distance which is based on a principle rather than setting defensive measure based on the cross of the sword.

| To choose the Measure of Proportion is to determine a proportionate and convenient distance from which the Swordsman can recognize the movements of his opponent, since for whatever determination of his, there should proceed, of body like of arm and Sword: Of body, by means of footwork: and of Sword, by means of the formation of the Technique. |

Restated, the Measure of Proportion must be chosen so that the fencer can recognize a threat from the adversary. You can anticipate the adversary’s actions if you provide yourself enough distance (and therefore time) to recognize motions of the sword or body.

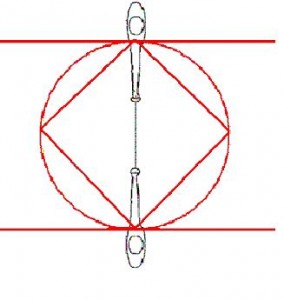

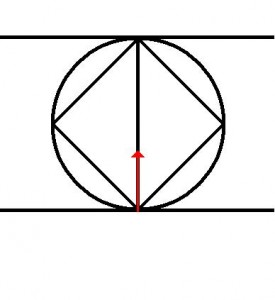

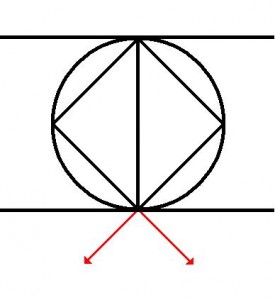

The Measure of Proportion and the Circle

It is important to remember that all the aspects of the Spanish Circle are defined by setting the Measure of Proportion.

The Measure of Proportion defines the Diameter which also defines the Circle, the Square, and the Lines of Infinity.

You should also note that when two adversaries have a different Measure of Proportion, they will have different preferred Diameters and the circle each wishes to create will be defined differently. This indicates again that arbitrarily “walking the circle” isn’t a reflection of the canonical Spanish tradition. Each fencer will attempt to create a more favorable circle which describes the possible footwork and counter-footwork in a fencing action.

As a common practice “walking the circle” would require not only two identical opponents with identical weapons, but also a choreographed plan in which neither fencer took advantage of the shorter distance gained when the adversary steps along the circle (as shown in Part 2). Instead the opponent would need to continually step away from the adversary to artificially preserve the ideal distance in the circle. Walking around a circle while within the striking distance of a non-cooperative adversary would be dangerous.

In order to close distance by stepping along the circle, the action should either control the adversary’s weapon as you move forward or take advantage of a Movement provided by the adversary (such as the thrust into the diagonal reverse shown in Part 1).

The Proportionate Measure (Offensive Distance or Place)

(En español – Medio Proporcionado )

This is the distance that must be covered to deliver a specific attack. For example the Proportionate Measure of thrusts will be different when using a pike, a sword, and a dagger. By using some of Euclid’s work we can provide a demonstration of which attack and position of the arm has the greatest reach.

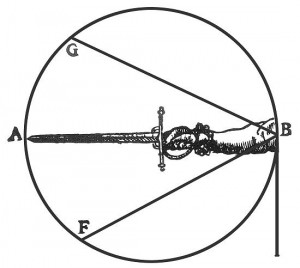

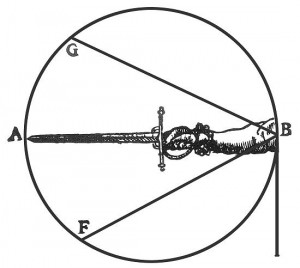

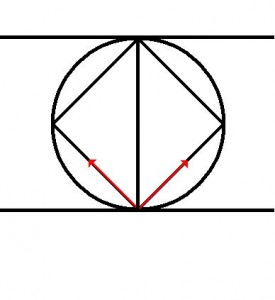

The Right Angle

Carranza demonstrates here that the Line from B to A has the greatest reach. This line is called the Right Angle and provides us with effective offense, counteroffense, and defense.

If the blade is lifted from the Right Angle, as shown in the line from B to G, we have entered the Obtuse Angle and our reach has decreased.

If the blade is lowered from the Right Angle, as shown in the line from B to F, we have entered the Acute Angle and our reach has decreased again.

Carranza uses Euclid to demonstrate distance.

The thrust typically has the most reach and will have the most favorable Proportionate Measure. In order to reach the correct distance to execute the thrust you may need to gain control of the adversary’s weapon and step along the Square (Transverse Step) or along the Circle (Curved Step). If the adversary prepares a cut, you can strike with a thrust into his preparation and then quickly retreat. By fencing with an extended arm, the Spanish fencer enjoys an advantage in the number of Movements (and therefore Time) when working against an adversary that cuts.

The Spanish cuts (both full circular cuts and the half cuts) are usually actions that occur when the blade has already moved from the Diameter because of a defensive action or because the adversary has deviated your weapon. These typically have less reach than a thrust but correctly executed can be very powerful. Ettenhard indicates that cuts to the head are more common and that horizontal cuts to the body are dangerous and unusual in practice. Because the Proportionate Measure of a cut is larger than that of a thrust, you should never use the cut as your initial action. The greater number of Movements in the cut expose you to counterattack by the thrust. (Remember that an advantage in the count of Movements is also an advantage in Time.)

The Disarm (Movement of Conclusion) requires you to be close enough to seize the adversary’s hilt with your left hand. This typically requires passing forward with your rear foot and the distance you must travel to successfully execute a disarm can actually carry you to the opponent’s Line of Infinity. Because the Proportionate Measure is greater for the disarm, there is a greater degree of danger involved for a fencer executing the disarm.

Final Notes

Remembering the Terms – The two terms Measure of Proportion (Defensive Distance) and Proportionate Measure (Offensive Distance) can easily be confused. At the risk of being slightly silly, I offer the following mnemonic to help remember the difference between the two.

“When asked of his defense, the aggressive fencer ate his opponent.”

- You can remember defensive measure because it has an ‘of’ in the term – Measure of Proportion

- You can remember offensive measure because it has an ‘ate’ in the term – Proportionate Measure

Angle as Position – The angle of the weapon (Acute, Right, or Obtuse) is a common way of describing the position of the weapon in space. You will see the same anglular terms used to describe position in Destreza texts for different weapons, such as the single sword and even Montante.

Filed as Classical Fencing, Destreza (Spanish swordplay), General, Historical Fencing, Italian Rapier, Movie Reviews, Opinion, Reviews with 12 replies

(8/24/2009)

LINK TO ARTICLE 1

In the Italian tradition there is an imaginary Line of Direction that describes the shortest path to the adversary.

The Spanish tradition uses this line and expands on the concept to create a 2D planar map of possible footwork laid out in a circle. The Spanish Circle is one of the defining elements of the science and various authors have presented it differently while preserving the core concept.

Carranza’s Circle

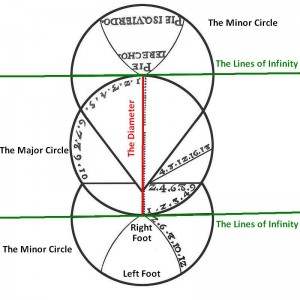

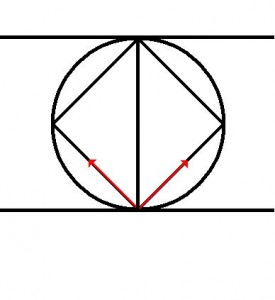

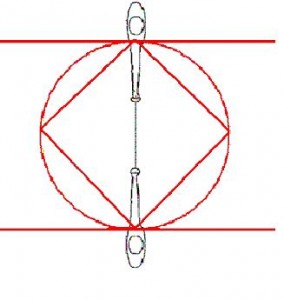

Carranza’s Circle from his text in 1569.

Here is the same image with labels to provide us a reference.

Carranza’s Circle with Labels

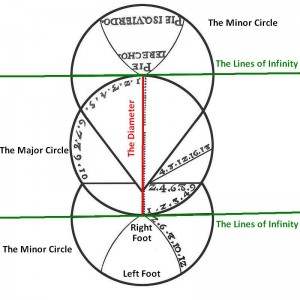

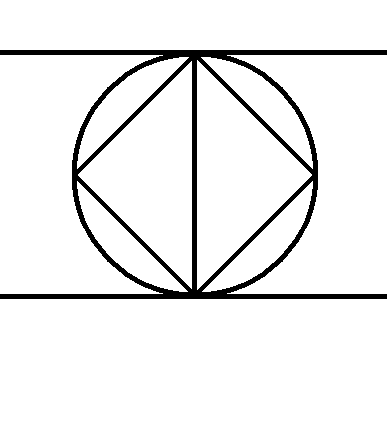

The Diameter – The imaginary line separating the two fencers is called the Diameter. It represents the shortest path to the target. The Diameter starts at the lead toe of the fencer (bottom of the red line) to the the lead toe of the adversary (top of the red line). The correct length of the Diameter should be the distance at which the fencer can observe the adversary’s offensive actions and still respond in time.

The Major Circle (Greater Circle) – The central circle shown between the two fencers is called the Major Circle or sometimes just the Circle. By rotating the Diameter about its center, we can create an imaginary circle which functions as a one piece of a footwork map.

The Lines of Infinity– The two parallel lines shown in green are called the Lines of Infinity or Infinite Lines. In the same manner as the Diameter, the distance between these lines is defined by your ability to observe and react to the adversary’s offense. Crossing the Line of Infinity means closing distance into the adversary’s offensive measure.

The Minor Circle – The smaller circles on either side of the Major circle are called the Minor Circles. The fencer and the adversary each stand in the center of a Minor Circle which is defined by the positions of the feet.

The Circle represents a moment of fencing time – The circle is not fixed in location, but instead describes the distance and possible steps within a specific fencing action. Just as the Italian Line of Direction changes when the adversaries move, so to does a new circle occur when the fencers change position. If an adversary has broken your defense and closed measure, the text may advise you to step onto a new circle and this represents the need to reestablish correct distance.

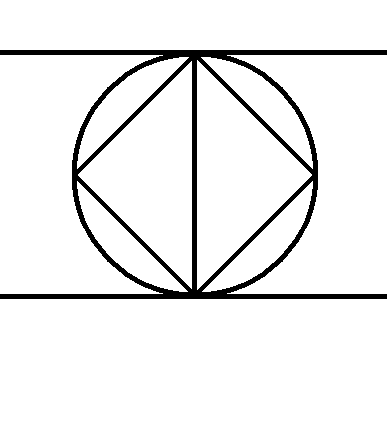

Pacheco’s Circle

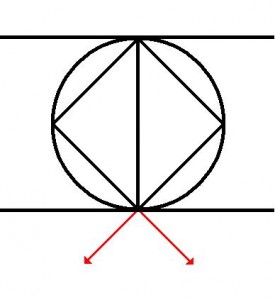

Later Pacheco describes a similar circle. Note that the origin point for the fencer is at one end of the diameter (bottom of the circle) while the adversary stands on the opposite side (top of the circle).

Pacheco’s Circle as shown in his book in 1600.

The primary addition to the Circle is the Square which like the angular lines above in Carranza’s Circle provide us with another indicator for footwork.

We can also map a series of vectors onto this planar diagram which allows us to precisely describe footwork. Remember that a vector is a line with direction and magnitude.

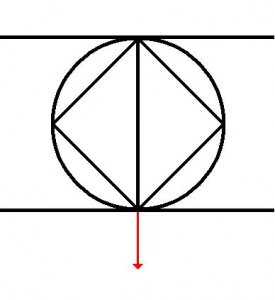

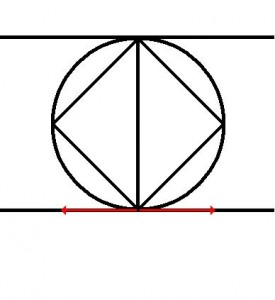

A vector that indicates motion to the right of the reader. (This vector has an undetermined magnitude.)

General Notes

The Spanish treat a step as a motion that starts in stance and ends in stance which requires a motion of each foot. When the fencer moves only one foot, this is specified in the description of the footwork.

To compare this to Italian fencing, we know that an advance starts in the guard and requires a movement from the lead foot followed by the rear foot returning to the guard. Likewise a retreat starts in the guard and requires a movement from the rear foot followed by the lead foot returning to the guard.

By contrast, when an Italian fencer executes a lunge, the fencer starts in the guard and moves only the lead foot. The final position of the lunge is not the guard.

Forward Step

(En español – Compas Accidental )

The fencer advances along the line of the Diameter.

Forward Step (advance)

Backward Step

(En español – Compas Extraño )

The fencer retreats in line with the Diameter.

Backward Step (retreat)

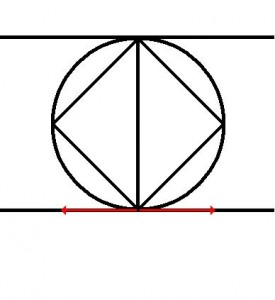

Lateral Step

(En español – Compas de Trepidacion)

The fencer steps along the Line of Infinity either to the left or right. When stepping towards a direction, unless directed otherwise, the fencer will avoid crossing the feet. For example, when stepping to the right, the fencer will lead with the right foot. When stepping to the left, the fencer will lead with the left foot.

Lateral Step (sidestep)

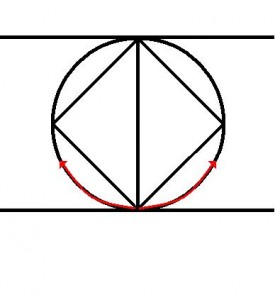

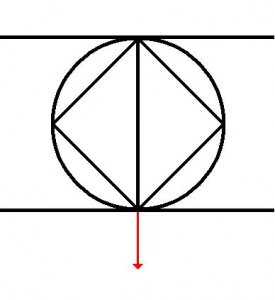

Curved Step

(En español – Compas Curvo)

The fencer steps along the Circle either to the left or right. When stepping towards a direction, unless directed otherwise, the fencer will avoid crossing the feet. For example, when taking a Curved Step to the right, the fencer will lead with the right foot. When taking a Curved Step to the left, the fencer will lead with the left foot. At the completion of the Curved Step, the fencer should be in profile facing the adversary.

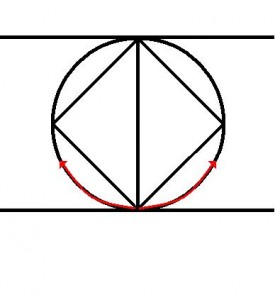

Curved Step

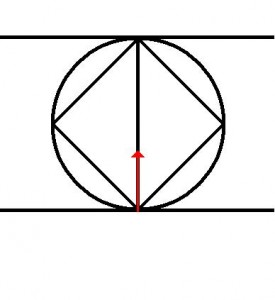

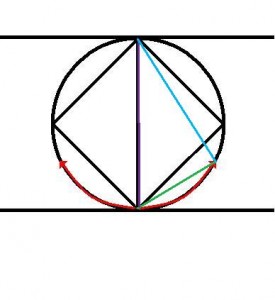

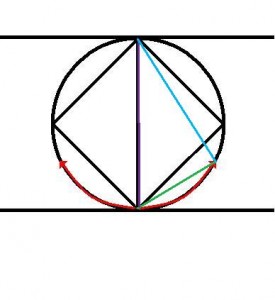

IMPORTANT NOTE: There is a misconception that stepping along the circle does not close distance. This is demonstrably incorrect as shown with this simple triangle in green, purple and blue overlaid on the circle.

The blue line of the triangle demonstrates the Curved Step has gained measure. The blue line is clearly shorter than the Diameter.

If you step along the circle you should be aware that you have entered the adversary’s range. Walking along the circle without reason provides your adversary with one unit of fencing time with each step and I don’t recommend it.

A Curved Step along the circle is a common method of gaining ground gradually and is often used in response to an offensive action from the adversary.

For example, if the adversary executes a cut, we may intercept the attack with the blade and then step forward along the circle to deliver a riposte. Because the adversary has moved forward already, our step moves only slightly forward and takes us off the line. After we have delivered a riposte, we might back away safely past the Line of Infinity.

Transverse Step

(En español – Compas Transversal)

The Transverse Step is a type of angular advance either to the left or right along the square shown inside the circle. The Transverse starts with the lead foot and is followed by the rear foot. At the completion of the Transverse Step, the fencer should be in profile facing the adversary. When there is an exception to this, it is stated in the description of the step and may be called a Mixed Step (See below).

Transverse Step (angular advance)

The Transverse Step closes distance more aggressively than the Curved Step shown above and is typical of offensive actions or attacks into the adversary’s preparation.

Mixed Step

(En español – Compas Mixto)

A Mixed Step is a combination of two other types and are often angular retreats either to the left or right away from the circle.

Two common examples of Mixed Steps are Mixed Backwards and Lateral to the left or Mixed Backwards and Lateral to the right. In this case, the Mixed Step starts with the rear foot and is followed by the lead foot. At the completion of the Mixed Step, the fencer should be in profile facing the adversary.

Mixed Step Backward and Lateral (angular retreat)

Another common Mixed Step is the Transverse Step to the Left using the right foot, followed by a Curved Step with the left foot.

Mixed Step Transverse Left and and Curved Left (angular advance with passing step)

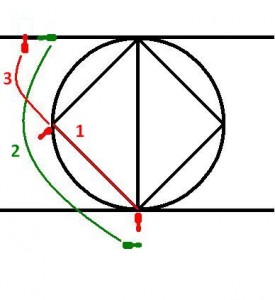

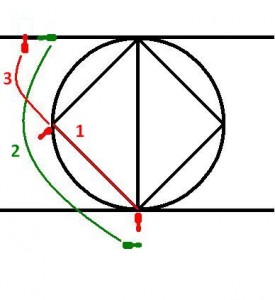

This image is my copy of a Circle from Ettenhard’s book in 1675 which describes the footwork.

1. The lead foot takes a Transverse step along the square pre-turning the lead foot to point back to the adversary. (The weight rests on the ball of the lead foot.)

2. Pivoting on the ball of the front foot, the rear foot moves in an arc landing on the adversary’s Line of Infinity.

3. The lead foot passes behind the left executing another pivot and placing the fencer in profile with respect to the adversary on his Line of Infinity.

Other Footwork

Other footwork is explicitly described in the text.

For example:

The Italian gaining step would be described as “bringing the rear foot forward close to the heel of the right foot.”

The Italian lunge would be described as “an extreme forward step of the lead foot while keeping the rear foot fixed.”

Opposition of Footwork

According to Ettenhard,

- The Forward Step is superior to the Backward Step

- The Forward Step is defeated by the Transverse, Curved, Lateral, and Mixed Backward and Lateral Steps. (Stepping off the Line of Direction will defeat an advancing opponent.)

- The Transverse and Curved Steps can be defeated with the Transverse and Curved Steps. (When an adversary circles toward you, either moving into them or circling away can defeat their action.)

Application to other Traditions

Again this material can be tradition agnostic. Using the Spanish Circle as a footwork map provides us with a useful guide for describing to a student how fast we want them to close measure. We can also advise the student to step inside the square or outside of it provide more nuance.

In addition, the Spanish codify angular and circular footwork which has been largely excluded from modern fencing traditions. As Ettenhard states, countering a circular step with a circular step is a good solution and we see this understanding in Destreza, Aikido, and many other martial arts.