Beauty in Destreza: The Golden Medio

What follows is the basis for the Golden Mean in philosophy and how it relates to Destreza. (If you want to find the practical application, you can skip to the end.) First, we should define the Golden Mean and we can start with a simple analogy.

Icarus flies with artificial waxen wings. If he flies too high the wax melts and he plummets into the sea. If he flies too low, the splashing water will weigh down his wings and he will, again, plummet into the sea. Only by flying the middle path will Icarus be safe.

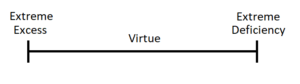

In the same way, Aristotle’s Golden Mean (or the medios) are virtues which exist as mindfully chosen points between two extremes. Aristotle lays this theory out in Nicomachean Ethics as a balance between excess and deficiency. Another key point is that medios are chosen mindfully and with consideration rather than as a habit or a natural response. (As an example, good manners are considered rather than pro forma.)

The medio pattern for the virtues is:

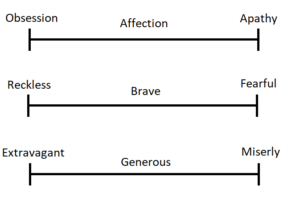

Here are some examples:

Maybe you agree with this formation of ethics and maybe you don’t but knowing this will help you understand True School Destreza. One of the critical phrases you will see in True School Destreza is “not participating in extremes”. This is an essential clue that we are talking about a medio and the tradition has plenty of them. (When I use a lowercase ‘m’ I’m referring to a general golden medio and not one of the Named Medios which will be uppercase ‘M’.)

Let’s consider some examples of medios in the tradition:

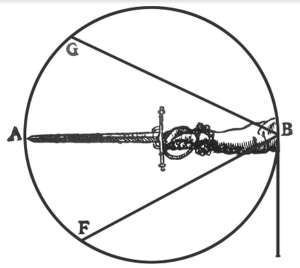

The Right Angle

Center-weighting

Hand Position

The Atajo

| “Atajo, according to our definition, is when one of the weapons is placed over the other (not in any of its extremes nor with any of its extremes) and with equal or some degree more of strength subjects it and makes it so that the technique that can be formed must be done with more movements and the participation of more angles than those that its simple nature requires.” |

~Pacheco’s New Science as translated by Mary Curtis (p.365)

Choosing Medios

Now we know what medios are but as to choosing well, how do we do that?

For that, I think we should consider Carranza and the role of Eudemio in the Carranza text. He is a young man excited about fencing but his mind is filled with many false notions. Through dialogue the other speakers persuade him into a process of action, an algorithm for true Destreza which Carranza outlines.

Consider this passage of Charilao’s in Carranza’s text:

What the aim of the Destreza is:

| “Because the Swordsman should first know and after having known to fabricate in the understanding with the declared parts what he should do against the adversary which is the goal in the art of defense, and afterward to look for the means that are best to achieve the intention, because what is first in the intention is the last in the execution of the demonstration, and this is understood in the swordsman who acts with deliberation for some purpose, which is not required in the purely natural agents because the action of these is that of nature: so the demonstration is divided by cause and by effect.” |

~Carranza as translated by Mary Curtis (folio 35r)

If there was ever a purer statement of LVD I have yet to find it.

To summarize:

- Knowledge – To know you must learn, you must study, understand, gain experience

- Perception – Understand the potential, see the possibilities, the paths forward

- Decision – From these possible futures choose the best

- Action – Bring the decision into reality through action

Carranza directly tells us that his book is intended to improve the young men of Spain. Swordplay is the mechanism he uses to present a method of thoughtful or deliberate action but we shouldn’t be deceived into thinking that he’s only talking about swordplay or even self defense but a path to a beautiful medio or virtue in the Aristotelian sense.

Later, our young protagonist, Eudemio, denounces the false fencing master of the text. At this point in the text he knows the truth because he has learned. He understands the potential paths forward. He makes a decision to tell his friends about the dangers of the false fencing master and he acts.

That’s Destreza. True Destreza, in my opinion, is most correctly the application of this process regardless of the specific system. The books provide us with a traditional system of swordplay that we can try to recreate but behind it all is the pursuit of the truth and the betterment of the world by mindful action.

To paraphrase Carranza each fencer is a musical instrument unique to itself. On each you must tighten some strings and loosen others until the instrument is tuned. Only then will it produce harmony. Fencers have different bodies, different weapons, different spirits, and different contexts. If the causes that form the fight change, the fencing must change as well. That’s expected.

Defensive Medio

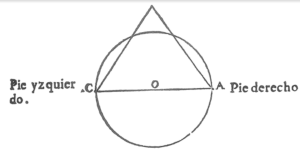

More than just a mark on the floor showing distance or measuring swords against each other, the Medio of Proportion (MdP) is a wholistic context in which the diestro gathers up many different causes, processes them using the system above, and then finds the correct place from which he or she can begin to form an offense yet still effectively defend. Balance extremes of offense and defense to find a defensible place to begin forming offense.

Practically Speaking: The simplest advice given here is to set your distance by measuring the swords against each other. The better advice is to set your distance such that you can still effectively defend yourself. If you are bouting and you are routinely struck before you can defend, you are setting up too close. Adjust your distance back until you are able to defend. As you gain experience and skill, you may find that your defensive medio changes.

Offending Medio

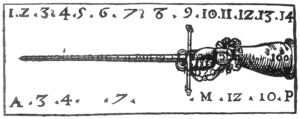

The Proportionate Medio (MPado) does the same but guides us in forming the attack such that we are protected. Balance extremes of offense and defense to find a place to strike while defended.

Practically Speaking: A well-formed attack should control either steel or time. If you have the adversary’s threat locked down with a bind, a conclusion, or some other physically detaining action then your attack is safe and achieves beauty. If you control the tempo because your adversary is moving dispositively you may strike in that during tempo of the movement. That’s also beauty. If you manage to provoke a defensive movement from the adversary with the right angle and you strike them with the Apropiado consideration that’s personal artistry and great fencing.

In Conclusion

When we fence and train within our context according to the causes then we may choose our medios well. That virtue is artistry and it creates beauty. When our instrument is in harmony with itself we can create music.

The True School of Destreza is not here to provide simple answers, instead it asks you to think about the context and find the answer yourself. By requiring the diestro to process the causes and choose medios, the diestro becomes an intellectual collaborator in the tradition. Suddenly the responsibility isn’t on the tradition to produce results but on the diestro to use science and skill to find them, to adapt knowledge, to challenge bad ideas, and always to strive towards something greater. Find the medio and you’ve found the truth, even if it is only for a moment.

(Credit to Charles Blair for providing me feedback which helped me correct some of my earlier work and arrive at this better understanding.)